If you were asked to name the top 3 human inventions or discoveries, what would those be? Well, for me it would be Wheels, Electricity, and the Internet. Electricity especially has been instrumental in industrial development and taking the human-race to where we are today. What do all the machines run on? How do the computers work? How are ACs run in the current heatwave? Electricity!

While India is gearing toward becoming the third-largest economy in the world, its Electricity consumption is also increasing at a very fast pace. Where does it all come from? Two-thirds of it comes from Coal. No wonder India (with support from China) took a strong stand at the recent COP-26 conference in Glasgow to soften the anti-Coal movement by the West and advocated a phase-down strategy than a phase-out strategy for Coal powered electricity. On the other hand, in the same COP-26 conference, India also pledged to become net-zero by 2070.

Can India really become a green superpower as it envisions to be? One might wonder if India actually has any strategy to achieve this or if it is just one of those false promises we see among today’s corporates? Before we delve into that, let us understand where does it get its power from.

India power industry

After China and the US, India is the third largest consumer and producer of electricity with nearly 400 GW generation capacity. Nearly 50% of this generation capacity is dedicated to coal-fired powerhouses. Only 42% of the total power generation comes from Renewable sources including Hydro, Solar, Wind, Bio, and Nuclear. Out of this, Solar contributes only 15% and Wind contributes 10%.

Considering the lower contribution of renewable energy sources, the target of becoming net-zero seems very tall, however, it is not a baseless hope. Why? Well, India does have renewable energy potential – 900 GW (which is more than double the total current installed capacity and 8x the renewable sources capacity). The majority of this, ~750 GW can be attributed to Solar, thanks to the 300 days of sunshine in a year (assuming 3% of the wasteland area to be covered by Solar PV modules).

While we are talking about the big opportunities and tall ambitions, we must first try to understand where we currently lie in this space and how much ground we have to cover to achieve such targets.

Solar value chain

While the current solar capacity of 60 GW is far away from the 2023 target of 100 GW, India has come a long way in its Solar journey. In the past decade, India saw a 50-fold increase in the installation base. However, this growth has been fuelled majorly by the imports of components from China. Nearly 75% of the installed photovoltaic (PV) module capacity was imported which contributed 4% to the country’s trade deficit during 2017-21. While India is encouraging corporates to do vertical integration across the value chain to reduce this dependency, it is not that easy. Let us understand why.

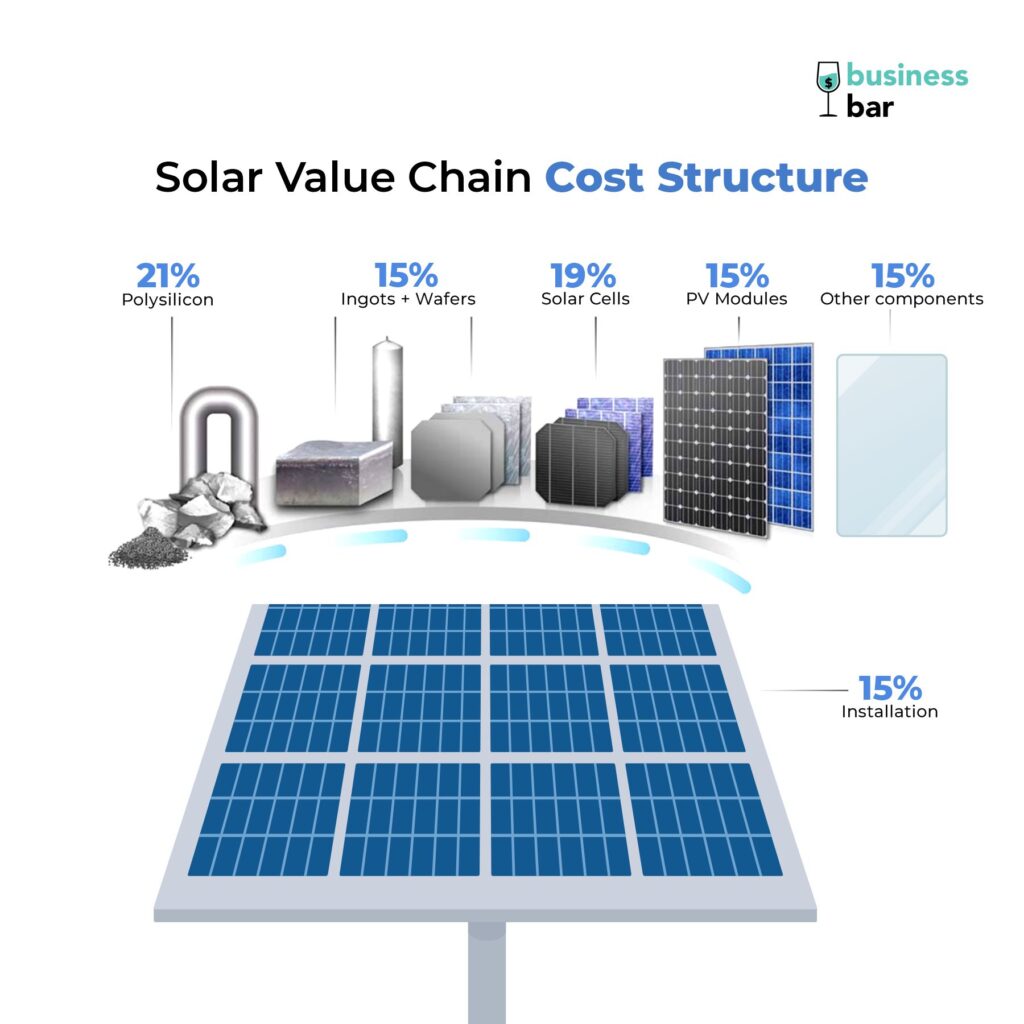

The journey starts with the mining of Silicon and processing it to produce electronics-grade Polysilicon. This Polysilicon is melted to form Ingots which are then subsequently cut into wafers. Then comes the most important where significant technical differentiation is required – the production of cells. The final part, the solar module is nothing but cells put together onto a glass sheet and connected to form an electric circuit. This is then distributed for field installation. In the entire process from mining to installation, modules make up for most of the cost (~70%) while other components and installations take the rest of the share.

As we go up the value chain from solar modules to cells to ingots/wafers, we see a sharp decline in India’s manufacturing capabilities since they involve high complexity and heavy capex requirements.

India has one of the largest module manufacturing capacities after China, thanks to the numerous mid-to-large scale companies such as Waree, Adani, etc. This is further expected to increase from 18 GW in 2022 to 110 GW by 2026 with many new entrants joining the race – Reliance, Shirdi Sai Electricals, Tata Power, and ReNew just to name a few top ones.

While Cell manufacturing still lags compared to Module manufacturing in the country, this step in the value chain is going to see the highest level of growth in the coming years. With big commitments from new entrants, the capacity is expected to increase more than 10x to 52 GW from the 2022 levels.Things change drastically when we move up the value chain – with only Adani having initiated the production of Inhots/Wafers. Other countries are no different as China virtually holds a monopoly in this space. China has 97% of the Wafer production capacity and 80-85% of the capacity of its raw material – Polysilicon. In the coming years, Reliance, Adani, and Shirdi Sai Electricals are likely to lead the race in the domestic manufacturing of Ingots/Wafers and Polysilicon.

As you may have predicted till now, all these commitments from the corporates have come after the push from the government through PLI incentives.

Production Linked Incentives (PLI)

The Union Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) allocated nearly Rs. 24K crores and 48 GW of domestic manufacturing across the solar value chain in 2 tranches since 2022. With an overwhelming response to the bids, this would bring an investment of Rs. 93K crores from companies, including big corporates like Reliance, Adani, and Tata.

However, these incentives alone cannot solve other problems such as red tape and nimbyism which hinder investments in the space. The government is doing well to address such issues by setting up clean-energy parks and reverse auctions to improve approval processes, attract investments, and lower costs.

Its positive impacts have started to show up with domestic as well as foreign investors enthusiastically committing to putting their money into the solar business in India.

Adani’s Mundra, one of the world’s busiest ports handling coal, is also set to become home to one of the biggest solar facilities in India. Adani plans to spend a whopping $70 Bn on green energy including Solar, Wind, and Hydrogen by 2030.

Not to be left behind in the Green race, India’s richest man, Ambani will be spending $80 Bn on clean energy. Its Polysilicon-to-Module manufacturing facility is also going to be commissioned at Jamnagar, which also houses the world’s largest petrochemical refinery of Reliance.

Notably, for the first time in India, First Solar – a US-based solar manufacturer received a PLI incentive of $143 Mn to set up 3.4 GW Polysilican to Module manufacturing capacity.

India has set two ambitious targets for 2030: to reduce emissions by a billion tonnes and increase non-fossil power generation 3x from 150 GW to 500 GW, which includes nuclear, hydro, wind, and solar energy. This is higher than India’s total current generation capacity of 400 GW. Achieving this target and becoming the world’s second-largest green power in just 8 years would require an estimated investment of $500 Bn in clean energy and grid improvements. How will things unfold for India? Let us do some reality checks while we stay optimistic about India’s solar dreams.

What lies ahead

Putting things in perspective

Increasing the renewables capacity from 150 GW to 400 GW though seems very ambitious, achieving such a feat cannot be called unprecedented. You guessed it right, China went from 44 GW of solar capacity to 300 GW in 6 years, and from 50 GW of wind to 330 GW in 11 years.

Though India lacks the advantages China had – a huge manufacturing base and investments flow, it seems to have started moving in the right direction. Solar seems to be winning the Sun vs Smoke battle in India where new capacity installed for Solar has surpassed that of Coal every year since 2016.

India’s cost advantage

It is not only the increasing demand and subsidies that are attracting investors to India. India also holds the potential to become the Solar manufacturing hub of the world thanks to the lower manufacturing costs. Discounting for government subsidies, India is the second lowest country after the UAE when we compare cost per MWh of solar-power generation. This also makes the new capacity installation of solar more attractive as compared to building coal-fired power stations.

Despite all the positives and optimism, India’s road to achieving this herculean task is not going to be easy. There are several challenges it will have to tackle along its journey.

Not so easy to defeat China

With 300 GW of Solar portfolio China controls 75-80% of the world’s manufacturing facilities from Polysilicon-to-module in the manufacturing value chain. Longi Solar, one of the leading manufacturers in China, has a module manufacturing capacity of 80-85 GW, which is higher than the combined capacity for all Indian companies. For Polysilicon, China’s Xinjiang province houses 40% of the global Polysilicon manufacturing capacity. The largest facility there alone manufactures one out of every seven panels in the world.

When nearly the entire world is so dependent on China, it will not easily give up its leadership to India.

Polysilicon to wafer process is technologically most complex and capital-intensive in the entire module manufacturing value chain. To sustain its position as a leader, China is reportedly mulling over banning the export of technologies and machinery required for Polysilicon/Ingot/Wafer manufacturing. If implemented, this would be a huge setback for the countries like India which are eyeing to achieve control over the most value-adding step in the manufacturing process. The result could be a sudden halt or significant slowdown for the integrated solar manufacturing plans of India.

Financing the dream

According to experts, India will have to invest nearly $500 Bn by 2030 to achieve its 500 GW renewable targets (including 280 GW solar). The current investment plans by big firms make up only about half of this requirement. This means attracting a significant pool of capital through foreign investors and other sources at times of global economic slowdown and increasing interest rates. The financial strain of big capital commitments on big corporates could also impact their appetite. The recent episode of the highly leveraged Adani group is a very relevant example of its vulnerability.

PLI a magic bullet? Maybe not

Through PLI policy, the government is firing all the guns at the same time – giving incentives and putting barriers to protect the industry. However, an increase in import duties to 62.5% would directly increase the input costs as long as India is dependent on China for Polysilicon and Ingots/Wafers. And to prevent Solar from being more unattractive than Coal, the exchequer and ultimately the taxpayers will have to bear these costs. The government would do well to ensure the indigenization of these parts of the value chain if we are to truly achieve independence in Solar.

Laggard in rooftop solar

India’s solar shortfall (40 GW capacity vs 100 GW target) is mainly in rooftop panels that the government expects to make up 40% of total solar capacity. Although overall capacity has increased nearly to its target, rooftop installation has been quite a laggard. Only 8GW (vs 40 GW target) was the capacity of rooftop installation in India. Though there were multiple reasons such as financing, net metering issues, and regulatory hurdles that prohibited the growth of rooftop in India, it is going to be very difficult to reverse the trend.

India’s second green revolution has just begun, and it has already taken its first steps. The West had a hundred-year lead in the traditional automotive industry, and India has slogged hard to catch up and compete. However, in the clean technology race, India does not face the same comparable disadvantage. It will be interesting to see how India achieves its 500 GW renewables target. Will it actually become the world’s second-largest solar superpower by 2030? Will it be nuclear energy that will fulfill its clean energy dreams? Or will India do for Hydrogen what China did for batteries?