“The Olympics remain the most compelling search for excellence that exists in sport, and maybe in life itself.”

-Dawn Fraser

The Olympic games are believed to have first started in the 8th century B.C. in Olympia, Greece. They continued to be held every four years for 12 centuries when they were banned by the new emperor. The athletic tradition was resurrected about 1500 years later when the first modern Olympics were held in 1896 in Greece. And that was the start of the modern Olympic movement as we know it. The first winter edition, which includes sports practiced on snow and ice, was held in Chamonix, France, in 1924. Since 1994, the Olympic Games have alternated between a summer and winter edition every two years within the four-year period of each Olympiad. Paralympics (originated from Parallel Olympics) is a competition that is now held alongside the summer games features specially-abled athletes.

Since the start in 1896, the games have only been canceled just three times: once during World War I (1916) and twice during World War II (1940, 1944). The Tokyo 2020 summer games could have been 4th on the list due to COVID-19, but the games are finally happening with all the planned 339 events across 33 sports, albeit a year late in 2021.

Fun Fact: Skateboarding, a not-so-popular thing in Japan, was added as an Olympic sport in the Tokyo 2020 games for the first time. On the other hand, the men’s marathon has been part of all the modern Olympic games. Speaking of which, here’s an explainer about what good marathons and bad investments have in common.

Years of sweat and practice of over 11,000 athletes from over 200 countries culminates at a megaevent that lasts for just two odd weeks. But the preparation of athletes isn’t the only thing that is at test at the games, it is also years of preparation of the ‘host-city’ that conducts the games. Naturally, hosting an event that has eyes looking at it from all over the world requires a great deal of detail and of course, money

What does it cost to host the Olympics? Who foots the bill? How much revenue do the Olympics bring? Who profits from the games? Are the Olympics worth it for the cities that host them? Well, if you share any of those curiosities, you’re at the right place! Let’s look at the economics of hosting the most-watched sporting event in the world!

Hosting the Olympics

One key player to know about before we delve into the financial scorecards of the games is the IOC. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) is a non-governmental sports organization that is the governing body for the entire ‘Olympic Movement’ – an umbrella term that encompasses everything relating to the Olympic games. (The IOC can be understood to be the Olympic equivalent of ICC for cricket or FIFA for soccer.)

Unlike World Cups which are hosted by entire countries, the honor of being the host of the Olympics is given to a single city every four years. Cities from around the world bid to host the Olympics. The bids are then scrutinized by the IOC and the host is then chosen. This happens at least 7-8 years before the concerned games are to take place. Once final, the city then gets to work to make the Olympic dream happen!

How much does it cost to host the Olympics?

With 339 events across 43 venues spanning 11,326 athletes, one thing is clear: hosting the Olympics is no ordinary feat. And same goes for the budget for the games. The cost of just bidding for hosting the Olympics is well in the range of $100M and goes as a sunk cost if the city loses the bid. Unsurprisingly, this whopping number dwarfs against the actual mammoth costs of actually hosting the games.

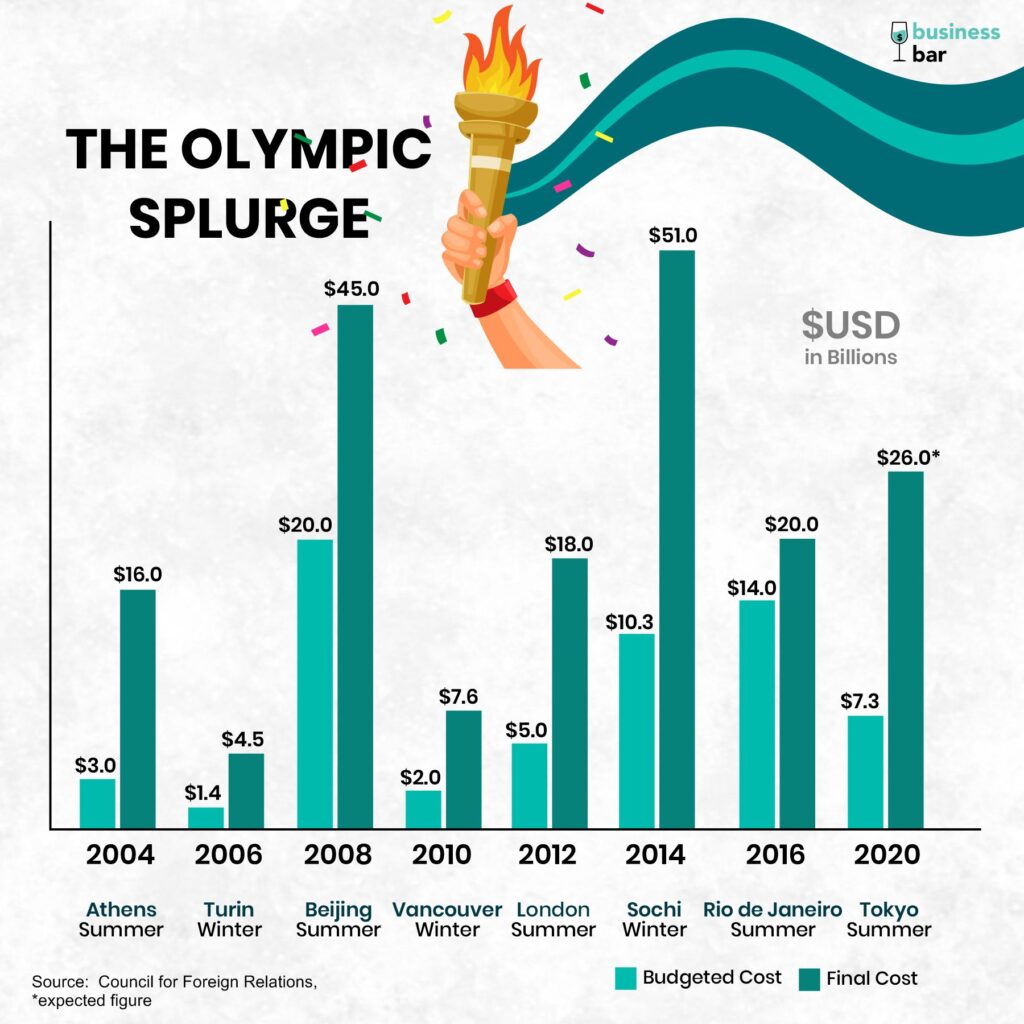

When Tokyo was awarded the hosting of the 2020 games in 2013, their bid pegged the costs of the games to be $7.3B. By 2017, the estimates by the organizing committee itself nearly doubled to over 1.4T Yen ($12B), and then again to $15.6B in 2019. The recent estimates suggest that the actual costs would land around $26B.

So where is all of this money spent? Short answer: many places.

The actual bill of the Olympics quite frankly depends on one thing: infrastructure spending. The IOC demands tens of designated venues for the hundreds of events and a primary Olympic village to house 11,000+ athletes. Although the world’s most populous city, Tokyo already had some of the facilities adequate to host the games, it still had to build 8 permanent and 10 temporary facilities. And the costs quickly add up.

The costs for building ‘Olympic size’ facilities can easily run into a few billion. The main Olympic stadium that hosts the grand opening and closing ceremonies was initially planned to be built at a cost of $800M as per the original bid documents. By 2015, the estimates ran well over $2B, owing to architect Zaha Hadid’s futuristic design. A decision was soon made to scale back the project with a new design by the Japanese architect Kengo Kuma. The 68,000 seating capacity stadium was finally completed in 2019 at a cost of $1.4B.

The IOC also requires the host to create an Olympic village where all athletes are housed during the course of the games. The cost of building the 21 buildings in the Tokyo Olympic village came at a price tag of $2B. The cost of building a media facility for producing and broadcasting the games alone can cost $0.5-1B.

And that’s not where the infrastructure costs end. Cities invest in non-sports-related development projects such as extending local transportation routes and security arrangements. These costs depend on the level of arrangements already in place and the level of spending the host countries are willing to do so as to ‘impress’ the world. Athens required a new airport for their 2004 games that made up a big chunk of the $15B it spent on the games in total. More than half of the Beijing 2008 budget of $45 billion went to rail, roads, and airports, while nearly a fourth went to environmental clean-up efforts. Security costs have escalated quickly since the 9/11 attacks—Sydney spent $250 million in 2000 while Athens spent over $1.5 billion in 2004, and costs have remained between $1 billion and $2 billion since.

As these costs added up quickly, up went the budget for Tokyo 2020 games. Moreover, Tokyo is not an outlier when it comes to overrunning the Olympic budget. Olympic cost overruns have become a norm for a few decades now, both for the Summer and Winter Games. In fact, every Olympics since 1960 has run over budget by an average of 172%.

The reasons for the budget overruns vary with each edition but there are also the usual suspects – construction delays, import taxes, and the good old corruption. The original cost estimates are made at least 7-8 years prior to the games and practical costs start piling up once execution starts. For instance, owing to the rise in construction prices in Japan, the Gymnastics Center for Tokyo 2020 planned to be built at a cost of $81M, came at an eventual price tag of $200M despite no big changes to the design. The 2014 Sochi Winter Games in Russia are believed to be the costliest games at $51B, are surrounded by claims of corruption to the tune of $30B by Russian politicians and oligarchs. After all, it’s the cost of doing business in Putin’s Russia!

Nevertheless, the 275 pager ‘Host city contract operational requirement document’ outlines the requirements in such great detail that it is almost impossible for the host to estimate the landing costs accurately. Hence, as the games approach, the host city’s focus shifts on delivering the games in all its glory, even if it means going over budget.

Where does all this money come from, you ask?

Well, each Olympic game is unique in the way expenses are borne by various stakeholders. It is because although the International Olympic Council (IOC) remains a consistent party, games are awarded to a city and not the country as a whole. Now depending upon the political framework of the host country, the costs are shared by various levels of government.

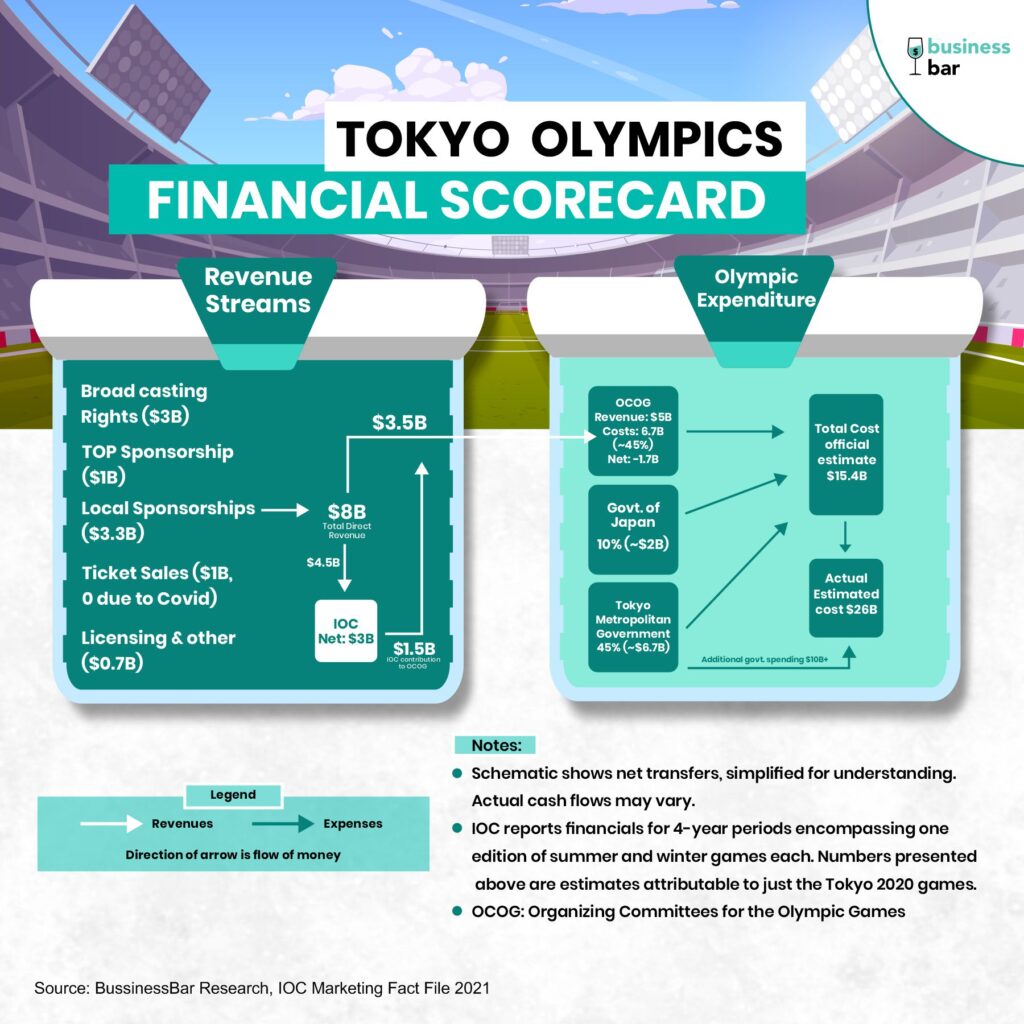

For example, in the Tokyo 2020 games, of the total cost estimated, 45% each will be contributed by the Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (Tokyo 2020) (OCOG) and Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG) respectively while the remaining 10% will be the contribution from the Government of Japan. But the OCOG comprises both the IOC and a few arms of the host country’s government.

Thus, the key takeaway from the complex web of bodies that host the Olympics is that it is the IOC that chips in only ~$1.5-2B for the games and the rest is on the taxpayers of the host country.

Then why do hosts spend way above initially planned budgets? Are the revenues good enough to cover such cost overruns? Let’s find out.

How does the Olympics make money?

The direct revenues that the games generate can be attributed to the following operations:

Broadcast

The Tokyo Olympics will be attended by athletes from 206 countries and thus it is no surprise that more than half of the world’s population is expected to tune in to watch the games. Olympic broadcast rights are thus one of the most sought-after properties in the media world. IOC in 2001, thus created OBS – Olympic Broadcasting Services, a wholly-owned subsidiary company that is solely responsible for producing and distributing the telecast feed for all events. For Tokyo 2020, OBS is said to produce over 9500 hours of content in just 16 days, out of which 4000 hours would be live.

OBS then sells the rights to broadcast this content in various geographies. The Rio 2016 Olympics brought in $2.87B from the marketing of the broadcast rights. The number could be higher than $3B for the Tokyo games but exact figures remain unclear as most deals are under review due to postponement of the games by a year.

Sponsorships

Sponsorship, as with most other sports, forms a lion’s share of the private money that flows into the games. The Olympic Sponsors can be chiefly categorized as follows:

The Olympics Partner (TOP) Programme:

The Olympic Partners (Programme) was created in 1985 and is the highest level of Olympic sponsorship. It is a deal between brands and the IOC, lasting for about four years, starting after the previous summer games are finished and ending with the following summer games. These brands are awarded exclusive rights to advertise and sell their products not only during the games in the host city but throughout the deal period across the globe. For the period of 2013-2016 that spanned the 2014 Sochi winter games and 2016 Rio games, 12 TOP partners paid $1B as sponsorship money. The current cycle has 15 TOP partners and the official sponsorship deal numbers are yet to be released.

Coca-cola has been an Olympic sponsor since 1928, being a TOP partner, it is the only option for non-alcoholic beverages at the games.

Domestic Sponsorships in the Olympics

Companies especially in the host country try to capitalize on the world’s largest sporting saga and thus rush to become sponsors of the games. And Tokyo 2020 has made a world record this time on the domestic sponsorship front. Tokyo 2020 has amassed a national sponsorship portfolio of over $3B that comprises no fewer than 62 Japanese companies. That figure does not include Bridgestone, Panasonic, and Toyota, three Japan-based corporations that are in the midst of multi-year, worldwide TOP partner deals with the IOC. The previous revenue record for domestic sponsorship was held by London in 2012, whose organizers generated roughly US$1.1 billion through their marketing program.

Ticketing Revenue

Although COVID-19 has severely impacted this revenue stream, the in-person attendance at various venues during the games have helped finance some part of the games. With 97% of the 8.5 million tickets available for the 2012 London Olympics, a total of $988M revenue was brought in. Japan is estimated to lose $800M on this front due to COVID restrictions. That translates to ~10% of total direct revenues that the games bring in.

Licensing

The IOC and the Organizing Committee for Olympic Games (OCOG) grant the use of Olympic marks, imagery, or themes to third-party companies to produce merchandise and souvenirs. Licensing programs are designed to promote the Olympic image and convey the culture of the host region. The Beijing 2008 games brought in the highest $163M from the 68 licenses granted under this program.

But whom does all of this money go to?

As with the costs, there are many parties involved. Also, the model is an ever-evolving one. Changes in the revenue sharing process are common for every four-year period for which the IOC documents its functioning. But to save you from the misery of the complexities and as we did with the cost burden of the games, we break down the revenues to just the two entities – the IOC and the taxpayers of the host country.

As per the latest Marketing Fact File, revenues from the sale of broadcasting rights, TOP programmes, and international licensing go primarily to the IOC. On the other hand ticket sales and domestic partnerships help reduce the government burden. Thus, out of the ~ $8B revenue from the streams enlisted above, at best only $5B will go to the Organizing Committee (OCOG).

Although similar to the case of the BCCI in the IPL, the IOC sits on a guaranteed surplus from the games. You can read BusinessBar’s IPL business analysis here. In fact, from the previous Olympiad 2013-2016 (4-year period containing one summer and one winter games) the IOC netted $5.7B. 10% of which is used for IOC’s administrative expenses and as IOC is a non-profit body, 90% is used as either contributions to the OCOGs hosting the games or is distributed to various sports associations and federations over the world for the promotion of the Olympic movement.

Every day the IOC distributes about USD 3.4 million around the world to help athletes and sporting organizations. – IOC filings

Back to the host city, even if the additional ~$1B from ticket sales would have been generated if COVID had not happened, it is clear that the direct revenues to the city are no match against the $20B+ that the Japanese government will have spent on the games. A recent study stated that Tokyo 2020’s economic loss would be $23B. And it is not a one-off thing. In the last 50 years, only the LA 1984 Summer games made an operational profit of $232.5M hosting the games. That success was largely due to the use of existing venues. Operationally speaking, the Olympics appear to be a financial nightmare for the host country.

Then why do countries host the games?

Intangible benefits or non-existent promises?

One might argue that there are other intangible and long-term benefits such as the boost to tourism and employment that might make sense of the games down the line, isn’t it?

Well, yes and no! It is definitely the story most hosts are told to convince themselves into becoming the hosts, but the evidence is not so encouraging in favor of the above argument.

The impact of the games on tourism has been found to be a mixed one by economists. Surely there are success stories such as Barcelona 1992 games that put the city on the map. The city jumped from 11th to 6th in Europe’s most visited cities after the games, and the developmental projects done back then on the seafront areas have attracted a lot of tourists to date. Sydney and Vancouver both saw slight increases in tourism after they hosted the games. The 2016 Rio edition helped Brazil bring in $6.2B in tourism-related revenue, just a 6% increase from last year. But London, Beijing, and Salt Lake City all saw decreases in tourism during the years of their Olympics. Such decline in tourism can be attributed to security risks, overcrowding, and higher prices.

As far as employment is considered, several studies have been conducted by economists about the impact of the games. The greatest criticisms that have come out of such studies is that the employment that is generated due to the games is more often than not temporary in nature and the majority of those employed are the ones who already had active employment previously.

There definitely is an upgrade in the city’s amenities such as transportation, often the projects made for the games do not serve the common city life, such as the metro lines to the Olympic villages that sit idle.

And adding to the woes of the city after the games are the so-called ‘white elephants’. The state-of-the-art facilities and stadium built for the games require millions of dollars a year to maintain and often occupy valuable real estate that then goes unutilized.

Add to that the fact that when debt is involved in financing the games, host cities are haunted by both the wreckages of stadiums and packages of interest payment dues. The $15B that Athens spent on the 2004 games was financed by debt and blamed for being the catalyst for the recent Greek debt crisis. The 1976 Montreal games featured the main stadium which was financed by debt and it took the Canadian taxpayer 30 years to get rid of that loan.

The dissatisfaction about hosting the games is pretty evident even with the ongoing Tokyo games. Authorities reported that it cost $1.6B in additional costs just to postpone the Tokyo 2020 games to 2021. Further, the fan-free situation caused by COVID restrictions saw over a million reservation cancellations in hotels and resulted in over $2B of lost revenue for just the 16 days of the games’ duration. A recent survey showed that more than 80% of the Japanese people oppose hosting the games even in 2021, due to COVID and the gigantic costs that the city has to bear for hosting the games. The public outrage is so tense that Toyota, one of the 15 TOP program partners of the Olympics, a deal reportedly in the range of $50-100M for the sponsorship, has decided to stop all Olympic-related advertising in Japan. COVID has unearthed the fault lines of hosting the Olympics and the world is taking note.

Will the Olympic torch stay alight?

Even after accounting for the intangible aspects, if Olympics are such a bad deal for the host cities then why are cities racing to bid for hosting them? The answer is, they’re not!

Twelve countries bid for the 2004 games that were awarded to Athens, six bids came in for the 2020 games and only two cities (Paris and Los Angeles) bid for the 2024 games. The IOC, understanding the adversity of the trend, made an unprecedented move and awarded Paris with the 2024 games and LA with the 2028 games (rendering LA a time of 11 years to prepare).

This award of two games simultaneously might have bought IOC some time to rethink the games but a systemic change is required. And that change can be seen coming with the new Agenda 2020 that the IOC launched for the next editions of the games. It drastically lowered the requirements for new venues to be built and focused on breaking even operationally, signaling more monetary contribution from the IOC. The cost of bidding for the Olympics which easily ran over $100M before will also be brought down to encourage more countries to bid. In fact, as per the new agenda, multiple cities and even countries can share venues for a single edition of the games, although such an event will not likely occur before the 2032 games which were recently awarded to Brisbane, Australia.

IOC’s new stand for the hosts is: “The games adapt to the host and it is not the host that adapts to the games”.

The changes proposed by IOC towards sustainability are still on paper and only the scorecards of the future editions of the games will tell how the new model fares! Interestingly, a suggestion of having a permanent host for the games doing rounds in Olympic circles. Thanks to the digital age, having the games at a permanent host can ensure that the games are brought to the whole world in real-time and in all its glory without burning billions of taxpayer money biennially.

Does the idea of a permanent Olympic host sound good to you? Let us know!

3 comments