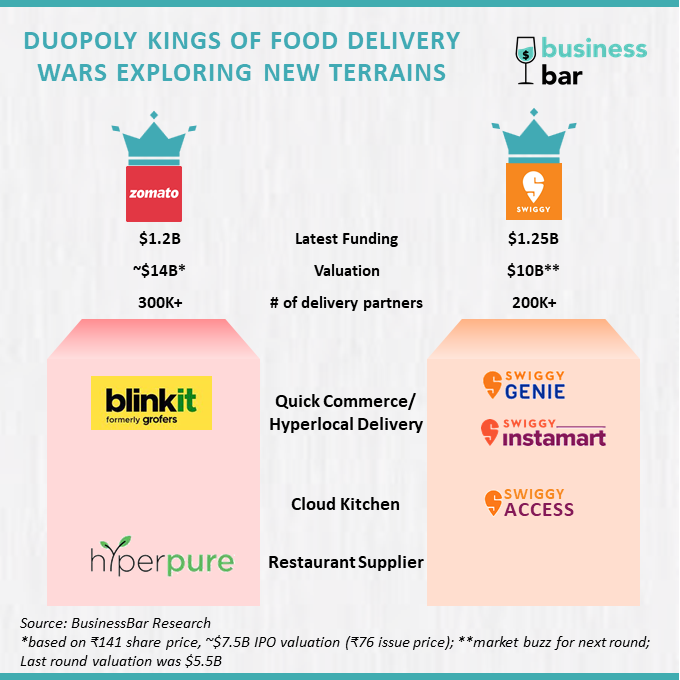

The decade-long food delivery war has resulted in two leaders – Zomato and Swiggy. However, these leaders are still bleeding losses and are looking for opportunities to diversify into other segments. Both the giants have managed to raise about $1.2B in 2021 alone – Zomato sourced through IPO and Swiggy from private placement led by SoftBank and Prosus.

The giants are massively spending on non-food business and plan to spend further in near future. Both of these giants want to leverage their moat of large fleets of delivery partners who have peak demands at mealtimes of the day and are mostly idle for the rest of the day. However, the giants have a different approach to organic vs inorganic growth.

Zomato expressed that it will follow the playbook of Chinese tech behemoths Alibaba and Tencent by investing in ecosystem players that will either lead to windfall gains or potential M&A opportunities. Zomato plans to invest $1B in the quick commerce segment in the coming years.

Swiggy follows a different approach by growing organically by investing in its verticals of Instamart, Genie, and reviving back the COVID impacted cloud kitchen vertical Access. Swiggy plans to double-down on Instamart with a $700M investment.

Why are these duopoly kings exploring new terrains? Despite the fact that the Duopoly markets provide an edge to make profits these giants are making losses. Let’s break this down to granular unit economics to find answers for profitability.

(You may also want to read our deep dive on another interesting duopoly in the aviation space – Airbus and Boeing)

Decoding The Food Delivery Unit Economics

As of FY20, things looked pretty bleak for Zomato and Swiggy. Zomato was losing ₹30.5 and Swiggy was losing at least ₹10 on every order delivered. Come FY21, and Zomato’s contribution increased to ₹20.5 per order. The FY21 numbers for Swiggy aren’t publicly available.

However, be cautious as a positive reported contribution margin doesn’t necessarily mean the company is profitable. This is because the reported contribution margin tells companies how much is left over to pay non-variable costs before taking profits. If we subtract the non-variable costs such as marketing and branding expenses/corporate overhead we are left with net EBITDA returns.

In the case of Zomato, despite the increase in contribution margin the EBITDA margin stayed negative 12~13% for FY21, and reported a -18% EBITDA margin in H1 FY22.

But how exactly did Zomato increase its contribution margin from -₹30.5 to ₹20.5 in 1 year? It was done by virtue of higher average order values (AOV) which increased from ₹282 in FY20 to ₹400 in FY21. The AOV for Zomato increased by 43% from FY20 to FY21. That number is 25% for Swiggy. The explanation for this increase in AOV, as claimed by Swiggy’s CEO, is the abrupt shift to work from home. Due to staying at home, food orders started taking place for at least 2 people, and single-user office orders vanished which caused the overall AOV to increase. This means that when people start returning to their workplace, AOVs are likely to go down to the level at which they were. Thereby dipping the contribution margins.

And this is what exactly happened, we could see the contribution margin of Zomato falling from 2.8% in Q1FY22 to 1.2% in Q2 FY22. While Zomato states that the dip is rooted in the increase in marketing spends to tier-4 and tier-5 cities. It could be evidently seen from the operational trends that Zomato is increasing its scale. Scaling up of operations coupled with easing-off of COVID would mostly lead to a lower AOV.

The second factor responsible for Zomato’s positive unit economics is higher commission charges to restaurants.

In FY2021, Zomato and Swiggy increased commission rates to 20% – 25%. Restaurants didn’t exactly welcome the increased commission rates, and 500,000+ of them convinced the NRAI to file a detailed probe against the duopoly.

It won’t be a surprise if the government imposes caps on these commissions to prevent food aggregators from squeezing restaurants. If there’s a limit on what food aggregators can make per order, their upside potential will be significantly limited.

And the final factor that led to Zomato posting a positive contribution is increased delivery charges from customers.

From FY20 to FY21, Zomato’s delivery charges went up by ₹11.7. In Q2FY22, delivery costs again went up by ₹5 compared to Q1FY22 due to unpredictable and prolonged rainfalls and a rise in fuel prices.

Even though the government might not cap the delivery charges, giants won’t be able to increase the charges as that might lead to a churn in customers. This is a major challenge as the switching costs are very low for the food delivery businesses.

Customers are likely to be loyal to a restaurant and not to a platform. What if Zomato provides you a 10% discount while Swiggy offers you a discount of 20%? Will you not switch? Of course, you will. That’s why to retain customers, there are loyalty programs Swiggy Super and Zomato Gold.Clearly, switching costs are low, and customer loyalty isn’t a moat.

The play for margins

Let’s have a look at some ways in which food-delivery businesses can improve margins and achieve business-market fit:

Option #1 – Pinch the delivery executive

Delivery platforms decide the delivery fee and a % of that is given to the delivery agent. Therefore, one way to increase margins is to adjust the delivery fee to maximize the margin for the platform at the cost of the delivery agent.

Option #2 – Pinch the restaurant

Food delivery platforms charge restaurants a commission – called the “take rate” – on every order placed via them. Therefore, another way to increase margins is to increase this commission %.

Now, food aggregators are dependent on these stakeholders for day-to-day operations and messing with them isn’t exactly a wise thing to do. So what’s a better solution?

Option #3 – Change the value chain

To better understand this proposition, let’s see the differences in the value chain of food aggregators & Domino’s.

Food delivery platforms are aggregators of demand. They stand between the restaurants and their customers.

Contrast this with Domino’s value chain.

Similar to food delivery apps, Domino’s aggregates demand. But unlike food delivery platforms, Domino’s has control over the supply side too. It negotiates with suppliers and sells raw materials to its franchise stores. This translates to lower costs and lower price volatilities in raw materials since Domino’s has high bargaining power against the suppliers.

Upstream the food value chain

In the current scenario, it is evident that the food delivery giants won’t be able to turn profitable only with the food delivery business. Vertical integration upstream is an option which both giants have explored. Swiggy has established 1,000 cloud kitchens for its restaurant partners across 14 cities in the country and spent a total of $24.5 million in Swiggy Access. Zomato invested $15Mn in Loyal Hospitality, a company that offers a platform to restaurant partners for planned exponential expansions without investments, and will be the sole delivery partner for the kitchens covered under the programme.

Food aggregators are adopting this vertical integration strategy with the supply side through cloud kitchens. It can be best explained by understanding Casey Winter’s “3 stages of a Marketplace” –

- Stage 1: Aggregate consumer demand, onboard restaurants (supply), and connect the two

- Stage 2: Own the delivery network, thus bringing the service to the customer. This enables food delivery platforms to identify popular dishes, preferences, ordering patterns

- Stage 3: Own supply by creating a cloud kitchen based on learnings captured from stage 2

HBS Professor Sangeet Paul Chaudhary sums it up best – “Restaurants take the risk of starting up. Delivery platforms learn from them and build more robust demand models than any individual restaurant ever could.”

Cloud kitchens benefit from:

- Lower rents

- Lower delivery costs as kitchens can be located closer to demand hotspots

- Lower costs of waste as demand can be predicted better

This is essentially a ‘platform-as-producer’ play where the platform competes with producers in its ecosystem.

However, cloud kitchens come with their own set of problems. Single-brand cloud kitchens have limited scalability as the customers are loyal to brands. COVID worsened the situation for duopoly kings as consumers prefer to order online from a well-known brand name due to health and hygiene concerns, even if it is slightly more expensive. Swiggy had to shut down three-fourths of their cloud kitchens and Zomato exited the partnership with Loyal Hospitality.

In order to achieve meaningful scale, cloud kitchens need to have multiple brands under their umbrella. Rebel Foods, the market leader, operates 450 kitchens with 20 brands.

In 2021, VCs have been pouring money into this Thrasio-style model, where a house of brands is created. Rebel food became a unicorn in October 2021 with $175M funding led by QIA (Qatar Investment Authority) at a valuation of $1.4B. EatClub raised $40M from Tiger Global in December 2021 at a valuation of $340M. Biryani By Kilo raised $35M from Alpha Wave Venture as it pivoted to consolidate the fragmented Biryani market. Wow! Momo raised $17M from Tree Line in September 2021. Curefoods raised $13M in August 2021, led by Iron Pillar, and it is now in talks to raise another $30M round.

Alternatively, food aggregators can negotiate with suppliers to procure fresh and quality produce and then deliver it to restaurants. This is exactly what Zomato is doing with Hyperpure. Hyperpure allows restaurants to buy everything from vegetables, fruits, poultry, groceries, meats, seafood to dairy and beverages from Zomato. It allows Zomato to widen its addressable market considerably, given that India currently has 70 Lakh restaurants and the bigger market opportunity comes from the 2.3 Cr restaurants in the unorganized segment, according to FHRAI’s estimates. The model seems to be working – over 9,000 restaurants are reported to be availing of the service. Hyperpure made Zomato Rs. 1B in revenue, a 49% QoQ increase and Zomato plans to invest over $50M in it in the next two years.

Downstream the delivery chain

Food delivery companies have a huge network of delivery executives, which are under-utilized because of infrequent demand. These can be diverted during non-peak hours to deliver non-food items which are in demand during non-peak hours.

Enter Quick commerce!

Delivering groceries and pick-up-and-drop services are venues that both aggregators have ventured in. As we’ve seen, these businesses struggle with making a profit and have high customer acquisition costs. This means they need customers to keep visiting them. Moreover, they have a massive delivery network that has perfected delivering food and isn’t utilized to its fullest – so they can sell low-value but high-frequency order items, thus unlocking even more value for customers. This converts these platforms into utility services and solves the problems we spoke of above – low customer loyalty & underutilized drivers.

However, they seem to be taking different strategies. Swiggy seems to be taking a full-stack approach. Swiggy launched its grocery delivery service, Instamart, with a commitment to deliver essentials in 15-30 minutes. Given the current growth trajectory of Instamart, it is set to reach an annualized GMV (gross merchandise value) run rate of $1B in the next three quarters, and Swiggy is investing another $700M in it. It also launched Swiggy Genie, its hyperlocal logistics service, which allows you to deliver or receive anything from documents to laundry. Swiggy’s COO, Vivek Sunder said that it aspires to be the “King of Convenience” by using its technology-fuelled logistics backbone to extend the convenience of food delivery to every other area. Zomato, on the other hand, is expanding via investments.

But quick commerce is not solved with just the moat of delivery partner fleet. It requires huge network of dark stores in addition to the high-tech algo to channelize the operations. This is all-over food delivery cycle again, where the market is swamped with large number of players fuelled with VC funding. Will the quick commerce turn into a duopoly like food delivery? Will the food delivery duopoly take over quick commerce? We’ll answer this in future round of industry pitcher when the time has unravelled the answer. For now we can say that Food Delivery giants are diversifying in search of profitability, let’s see where they find this.

This piece is contributed by Gaurav Maniyar