It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness…

These are the opening lines of the masterpiece ‘A Tale of Two Cities’ written by Charles Dickens. It best summarizes the amount of capital that has poured in and the company valuations since 2021, in both public and private markets. On one hand, India created 44 unicorns in 2021 and had stellar IPOs of Nykaa and Zomato. On the other hand, many of these investments were at ridiculously high valuations with shaky/unproven business models.

One such trend is the emergence of ‘Thrasio’ clones in India. Just in 2022, big-league players like Tiger Global, Alpha Wave (Falcon Edge), Flipkart Ventures have poured in over $500 Mn in this space. One would argue getting big cheques in a hot sector is nothing out of the ordinary in this funding frenzy fair. The highlight here is that almost all of the players are less than a year old. India’s very own Thrasio replica, Mensa Brands became the youngest unicorn within 6 months after launch.

Why has the Thrasio model gained so much momentum? What is the ‘house of brands’? What makes the changing D2C landscape so attractive to these players? How do the incumbents (FMCGs, conglomerates) plan to be up to date with the trend? We’ll answer these in this piece.

What is the Thrasio Model?

Thrasio, a US-based startup, was founded by Carlos Cashman and Josh Silberstein in 2018. It has raised $3.1 Bn dollars in funding to date and has made $1 Bn in revenue in 2021. While this sounds like a typical rant of an American startup, the surprising thing to note here is that Thrasio is actually profitable. It had a net profit margin of 20% in 2019.

Thrasio operates on a simple model. It acquires small consumer brands which sell on e-commerce platforms like Amazon. It then grows them with the help of capital, marketing and supply chain. Now, Thrasio has 200+ brands under its umbrella.

On the surface, this sounds like a private equity kind of structure, however, there are certain differences. The biggest of them is that Thrasio is eyeing to become a conglomerate that operates multiple brands.

Unlike a VC ,their focus is not on the exit but to become the new age P&G/Unilever.

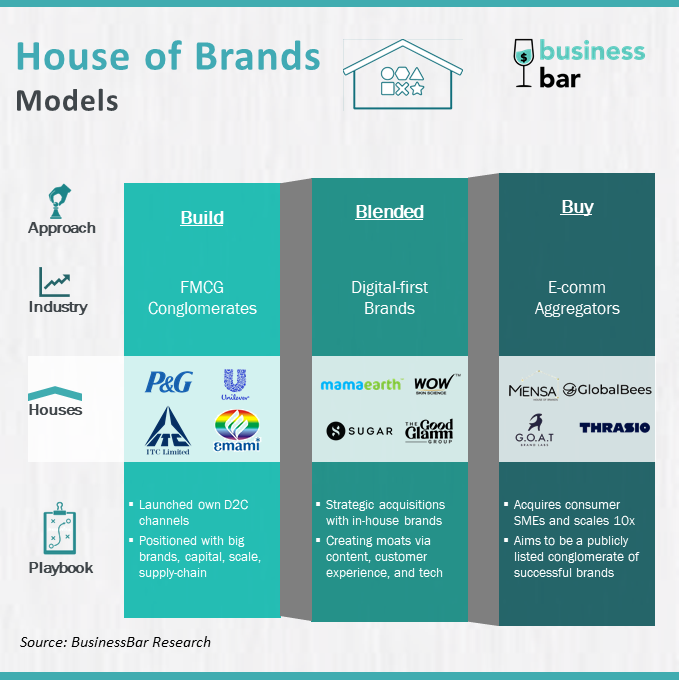

House of Brands and Build-vs-buy

To start with let’s look at Unilever and P&G, the pioneers of the house of brands strategy. These FMCG giants have been successful in creating massive brands which transcend borders.

However, their playbook has not been able to keep pace with changing consumer needs. Between 2015 to 2020, P&G, Britannia and Godrej each launched only one new brand in the Indian market. Emami did literally one better, by launching two brands. The massive white space along with internet penetration, online shopping and pandemic led tailwinds have propelled the growth of the Direct to Consumer (D2C) sector.

Traditional commerce is very expensive due to the multi-layered supply chain network of wholesalers, distributors and retailers. With the rise of e-commerce, products can reach the end consumers in under 3 days for 20K out of 26K pin codes in India. The new-age players have not only reduced the time to reach consumers but also reduced the time to scale.

For example, Boat Electronics achieved ₹100 Cr revenue in less than two years, while the beauty giant MyGlamm did it under three.

Now, Thrasio clones have sped up this process one step further by buying the small digital-first businesses. This is a stark contrast with the build strategy of traditional FMCGs. The Thrasio model companies have thus come to be known as e-commerce aggregators/roll-up players (these terms are used interchangeably in this piece).

How big is the D2C opportunity?

The D2C sector of India is expected to become a $100B opportunity by 2025.

What makes the Indian consumer goods sector unique is that it is vastly unbranded. Barring consumer electronics, as much as 80% of sales in other consumer categories come from non-brands. India has been historically a price-conscious market making the Indian retail market brutal. What’s more, the sales of many players plateau, which makes scaling all the more challenging (stay tuned till the next section for the answer).

For example, Amazon had only 4000 sellers in India with annual sales of more than ₹1 Cr out of a total of 850,000+. Comparing this with the home of Thrasio, the US – Amazon had ~20,000 SMBs with $1 Mn+ (₹7 Cr+) sales.

This is where the e-commerce aggregators like Mensa Brands come in. They bring their expertise in e-commerce, provide capital and leverage resources pooling across multiple brands. And voila! These aggregators are growing their brands at 100% y-o-y and are looking for a 10x growth from them. To scale the brands, aggregators have also started building an offline presence.

To understand their operations, let’s look at things from both sides of the table. On one side we have the brands and their founders who are selling their businesses and on the other, we have the e-commerce aggregators.

What do brands and founders want?

As discussed above, many online sellers typically hit a ceiling on the topline. Growing a consumer brand need two things – marketing and capital (to unlock economies of scale). While the founders are good at sourcing and manufacturing, they lack the experience of branding and massive capital.

VCs have brand-building expertise and there is no dearth of funds in the market. Despite this, it is hard for brands selling on Flipkart/Amazon to get a VC cheque. The reasons are twofold.

First, VCs want to invest in a high growth business, whereas the sales for these brands have plateaued. Second, VCs want exposure to consumer companies that have product differentiation and can create moats. It is difficult for a small player to create moats when you sell commoditized products (which is the case for most of these Amazon sellers) compared to branded products. Many VCs also have hard criteria of ~40% sales coming from the brand’s website rather than e-commerce platforms.

Aggregators also don’t want brands that have been touched by VC firms. The simple reason is that the VC firms offer a far higher valuation multiple on revenue compared to 1-2X revenue multiple offered by aggregators. Unlike VCs, these aggregators take a majority stake and sometimes go on to fully acquire the brand.

How much stake do these aggregators own? That depends on the aggregator, brand and founders. Especially, for businesses that have a niche consumer base or those that have deep founder connect, the aggregators structure the deals to retain the founders. They opt for a gradual and tiered exit payout for the founders, giving the founders upside potential.

The founders face a dilemma of scale vs ownership. “Ultimately, the value of an exit boils down to two metrics—the size of the pie and the size of the slice. So, a founder can get a life-changing exit by either having a small piece of a large pie or a large piece of a small pie.” –The Ken

Inside India’s E-commerce aggregators

For roll-up players, it is a three-piece puzzle: raising capital, picking the right brands and execution.

1. Raising Capital

Like a PE fund, you need to have upfront capital if making an acquisition is the first step of building your business. And similar to a PE fund, you need a team of seasoned professionals on whom the investors can put their money. Now, with this in mind look at the pedigree of some of the founders of Indian aggregators.

Mensa Brands was started by the digital mogul Ananth Narayanan, ex-CEO of Myntra and co-founder of Medlife. Firstcry’s co-founder Supam Maheshwari and seasoned finance leader Nitin Agarwal started GlobalBees (parent: Firstcry). GOAT Brand Labs was started by Rishi Vasudev who was an ex-senior executive at Flipkart and ex-CEO of Lifestyle International.

GlobalBees joined Mensa as the second unicorn in this sector within 9 months. It raised a funding of $100 Mn at $1.1Bn valuation led by Premji Invest. Thrasio finally entered India in 2022 with its maiden deal with Lifelong. Moreover, Carlos Cashman (CEO, Thrasio) has made a $500M baseline commitment for the Indian market. He also expects the Indian market to bring double-digit contribution to the overall topline in the next 12-24 months.

As far as capital availability is concerned, all of the players have raised big seed and series A cheques for the initial capital deployment. The next test will come when these players have to raise further rounds for which they will have to deliver on the growth pitch that they made to the investors.

2. Picking the Right Brand

After having the funds, finding the target brands at the right valuations becomes critical. To ace this game every aggregator has created an internal toolkit. This starts with having a category focus. Based on the founding team background, each player focuses on a few key categories. For example, Mensa Brands has three key categories: fashion, home and beauty-personal care. 10club has a strong focus in the home D2C category and has multiple investments in the home care brands.

The next is the scale of the brand that is being acquired. Mensa, the biggest in India, acquires scaled brands that are in a range of $1-10 Mn in annual revenue. GOAT Brand Labs targets players in the $1-$5 Mn annual revenue range.

The next item on the checklist is profitability. As we noted earlier, Thrasio is already profitable. And this is the exact same pitch that Mr Narayanan of Mensa has made: “Within the first six months of operation we’re actually profitable, and we continue to intend to run this business in a profitable manner”. The reason for this is that profit margin is a key consideration that goes while evaluation.

GOAT Brand Labs has already acquired 10-12 brands within 8 months of operations. Mensa has acquired 15 brands and it plans to double down on this number taking the total count to ~45 by 2022 end. To funnel this crazy inorganic growth, the roll-up players are closing the deals anywhere within 30-45 days from the first meeting.

3. Execution

A founding team with a strong operating experience of building consumer and digital businesses is a common theme that runs across all the roll-up players in the landscape. The lack of operating experience in the Indian market is one of the key concerns for Thrasio if it wants to fulfil its Indian dreams. To solve this problem, for now, Thrasio’s deal with Lifelong has a multi-year structure where Lifelong’s founder Bharat Kalia will lead Thrasio’s operations in India.

The likes of Mensa and GOAT Brand Labs handhold brands with their digital journey. They help brands with digital marketing, sales, growth hacking and inventory optimisation. Network connection of aggregators within the e-commerce industry also helps in speeding up the processes like getting listed on a new eCommerce platform like Nykaa.

The aggregators are building central functions like common warehousing and customer support which are used by all the brands in their house.

A parent entity owning multiple successful brands which have synergies across different businesses, is where an aggregator will land up if it checks all the three things above. This brings us back to the introductory question on the digital house of brands.

Rush to the Digital House of Brands

D2C Brands

The Good Glamm Group was started in 2017 by Darpan Sanghvi as a beauty brand MyGlamm. It now operates as a digital house of brands and is creating an entire ecosystem to power its D2C business. It also unveiled The Good Creator Co (GCC) to focus on content-to-commerce strategy. The company has also made great strides in building its offline presence.

The group operates home-grown brand MyGlamm and has since gone on an acquisition spree to acquire POPxo, Plixxo, BabyChakra, The Moms Co, ScoopWhoop, St Botanica, MissMalini, Sirona Hygiene, Vidooly, Winkl and Organic Harvest. Two of these mergers have also resulted in Priyanka Gill (POPxo, Plixxo) and Naiyya Saggi (Babychakra) joining as co-founders of The Good Glamm Group.

The company entered the unicorn club in November 2021 with a $150 Mn fundraise led by Prosus Ventures and Warburg Pincus. At the timing of this article, the company is looking to raise another round at almost 2x of the previous valuation.

MyGlamm is not the only one to consolidate multiple brands under one name. The same story is being played by other Indian D2C brands. Apart from the scale and cost synergy benefits discussed earlier, having multiple brands under a single house expands the company’s reach by allowing catering to multiple demographics. For example, HUL has four soap brands – Lux, Pears, Lifebuoy and Dove – which cater to different segments.

Purplle acquired cosmetics brand Faces Canada and it now operates Good Vibes, Carmesi, NYbae under its roof. In 2021, Velvette Lifestyle, the parent of SUGAR Cosmetics, launched a new skin-care brand Quench. WOW Skin Sciences and Mamaearth also operate multiple brands. Nykaa is also betting big with its range of in-house labels.

The house of brands phenomenon wave has touched other sectors as well. Rebel Foods is the pioneer in the food-tech segment and operates 45 brands in India and the world. Curefoods by Ankit Nagori operates 20 brands in its portfolio.

FMCG Giants are catching up

The FMCG giants don’t want to lag behind. FMCGs are hiring tech-savvy talent with backgrounds in e-commerce. Most of the big players have either launched a D2C channel or are in the process of launching one. HUL leads the chart, with 15% of its total sales coming from digital in Sep’21 quarter.

FMCGs are also using the ‘buy’ strategy to stay with the curve. Marico has acquired stakes in Beardo and Just Herbs, Emami in The Man Company, Colgate Palmolive in Bombay Shaving Company and Parle in ASAP Bars. The FMCGs already have the capital, scale and supply-chain networks. All they need is speed both in terms of strategy as well as implementation.

Future of E-commerce Aggregators

Both the digital house of brands and e-commerce aggregator model is new to India and there is very little data to see what will happen. India being late to this party has some perks, we can turn to other markets to see what is happening.

In the US, there are 70 companies that have a model similar to Thrasio. They have collectively raised $9 Bn dollars. However, the wave seems to be dying off. Some aggregators have already started struggling. “We’ve had several companies offer us their portfolio.” – said Ryan Gnesin, CEO of Elevate Brands, a Thrasio competitor. Thrasio has also delayed its plan to go public via SPAC due to high profile exits of its co-CEO and CFO from the company.

In Europe, investors put $1.1 bn in this sector in a single day! Yes, this will take some time to digest. The European market already has 20+ players operating in the space. Some experts are already calling this a bubble.

When Thrasio started in the US, the valuation multiple was estimated to be 1.7X of EBITDA. Now, the deals are happening at as high as 5-8X of EBITDA. Now, there are only a limited number of brands that fit the criteria of good product fit, growth potential and profitability.

The Indian market can face a similar challenge. The valuations in categories like skincare are already multiple times of revenue due to the increased interest of FMCGs, VCs, aggregators, and D2C giants. Along with this, debt financing to SMEs is getting simplified and easier day by day. More brands will take other routes of financing as Revenue Based Financing and Venture Debt Financing become more mainstream.

Similar to a VC, the upside for a roll-up player will come from the growth. Strategy actions like turnaround, growth and synergy creation are always easier said than done. The brands also have a huge dependency on e-commerce platforms.

Having said all this, the Indian startup ecosystem has fought long and hard battles and have emerged stronger. This sector will also fight its own battles. Both the Indian aggregators and the D2C players have IPO ambitions. They have the ambition to take Indian consumer brands onto the world market. Barring a few setbacks, we believe the sector is destined to be victorious.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the time when startups became conglomerates, it was the time when conglomerates became startups…

We thank Siddhi Kasliwal for her insights about space.